2008

by Swim

I first tried reading VALIS back in 2008. I was crashing with a lesbian couple “down the shore” in Jersey, broke and in between apartments and lives. I remember reading it in the shadows of their manicured yard and becoming intensely frightened, eventually putting the book face down next to my freshly painted toes and then pushing it further away. It was like reading about my own busted life in the state in which it existed exactly at that moment. Not only did it reference things I’d been legit just thinking about earlier that day or week, but it captured the flow of my thoughts--the frenetic rhythm at which my thinking moved from one increasingly insane association to the next. Like Horselover Fat, the protagonist and alter ego of Philip K. Dick, I was an actor playing two parts—one in which I knew I was fucked in the head and another in which I was secretly ok and it was the rest of the world that was screwed. Nearly a year earlier I’d surprised everyone by abruptly quitting a well-paying job and living off cans of soup, fake saltines and peanut butter protein bars with the goal of working on my novel until I could no longer pay the rent on my Manhattan studio. At the time, quitting the office gig seemed completely obvious as I was convinced the bookend event to 9/11 was immanent and this whole degraded way of life was about to be tossed asunder, to which I held up two middle fingers and bade it Good Fucking Riddance--but seeing as how I barely knew how to cook let alone survive off-the-grid, I figured it was now or never to contribute to humankind through my writing. Soon I’d be gone for good, with only these words and my internet search history and my student loan debt left to my name. I holed up and wrote and revised endless drafts about a reclusive woman who entered trance like states when she smoked a specific blend of weed and drank just the right amount of strong black coffee in which she drew symbol laden doodles that predicted disasters before they happened. She knew as she was drawing them that the images meant something, but they were too vague, and it wasn’t until after the terrible event took place that she was able to put the clues together. Soon I had hundreds of pages, which felt like something, but when I read it back it was so dark and hopeless. I couldn’t figure out a way of leading the character to a resolution. She spent all night drawing and all day searching the internet on their laptop while cable news played nonstop on their TV. But like me there was nothing that told them how to save anyone with the information they had. I kept going because sometimes the way out was there when I woke up in the morning, a bright little spark radiating from my chest, and I’d type like crazy and let it flow and get close to being able to put it into words—a sentence or two here and there wasn’t total shit and seemed to hint to the plot turn that was needed. But it always slipped away.

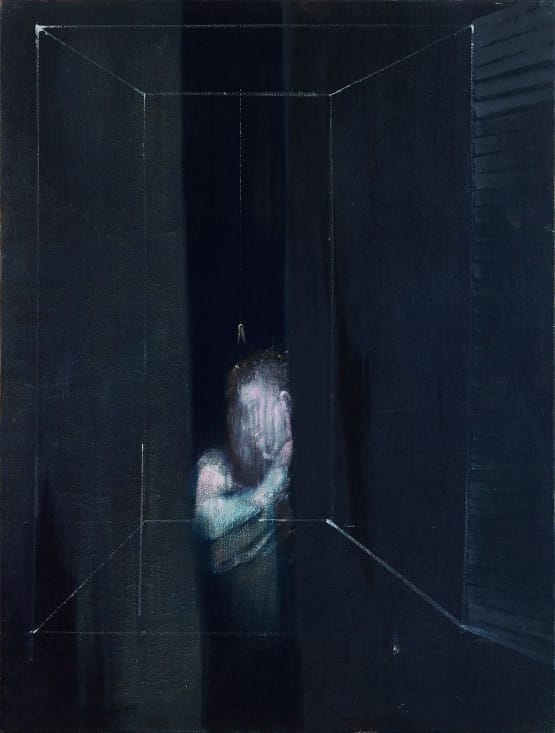

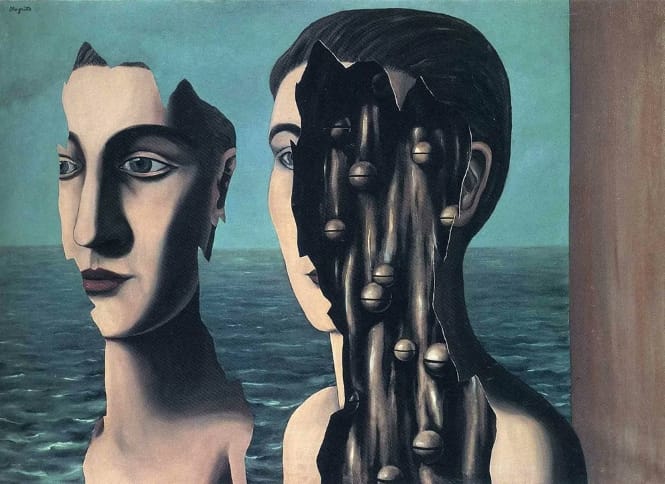

Winter turned into spring and as I sat at my desk, my eyes burning and my stomach sizzling, I felt a presence looming behind me. Out of the corner of my eye I could see the branch of the Callery Pear tree that stretched across the fire escape, a presence that meant nothing to me during the day, but late at night its newly bloomed glowing white flowers seemed to turn into demonic faces stretched in laughter. If I turned to look at them straight on, they became flowers again. It’s a trick of peripheral vision I told myself, coupled with the disorienting effect of the almost supernatural bright white of the flowers; but as I tried to work, I couldn’t resist stealing a look out of the corner of my eye, and there they’d be, what I came to regard as the flowers’ true nature—long, ancient faces like in an El Greco painting, some of them just watching, while others leered, open-mouthed and grotesque. I kept the window closed and the shade drawn, which worked for a little while, but I could still feel them out there, the branch tapping the window and those alien ghosts mocking me. It got so that I couldn’t stay at my place at night, and when I ran out of dive bars and moldy clubs that tolerated me slinking around without spending money on drinks, I left the city and went to stay with the lesbians, one of whom was the kid of my dad’s friend, and the only people who would put up with me because they not only lived in another state but another reality, one that included weekend climbing trips and lawn doctors and not one but two cars to cheerfully wash and dote upon like they did with their large black lab who lived with more health and humanity than several people I knew. They smiled at me a lot and never mentioned the smell of weed coming from my room morning noon and night while also carefully labelling the food in the fridge and “giving me my space” which included never inviting me to hang out to watch a Yankees game unless I was already in the room and even then it seemed like it was better if I left. Moving out to the beach was supposed to be a new start--I had a brainless temp job doing filing in a back office and I’d started half-assed therapy with someone who had all their degrees hanging on the wall, and when I reported to my family that I was saving money they acted like I’d won a gold medal. But none of these things, including the actual bright moments like the multicolored evening sky I stared at every night or the Mexican spot where I got dinner that also sold Mexican coke and KitKats, helped with any of the core issues that were fucking me up, and VALIS made this glaringly clear. Like Horselover Fat, I was caught in a loop. My nervous system was fried, and I was too attached—smothered, really--by my self-assigned role as caretaker to people I was never able to help anyway. Horselover Fat and I wanted to fix others so they wouldn’t leave us and cause us pain. We fronted like good people but really, we were just selfish sad sacks. That PKD had sketched out my being to such perfection was too much. Nope, I said, and put the book down (eventually zipping it into a side compartment on my suitcase and leaving it there forever, along with my stank gym sneakers) because I was afraid for how it seemed likely to turn out for Horselover Fat--and for me—the former a self-anointed seeker and the latter a wannabe writer with an attention span which was by then so clipped I could barely string together a complete sentence, who both thought that despite of and because of their myriad failures they were on to something uniquely REAL but were most likely just lunatics.

In 2008 I thought about killing myself all the time, or at the very least once a day as soon as I woke up, but rather than going through with all that detailed planning, I instead offered myself up in a series of sexually intense and emotionally degrading relationships, my open heart a bloody offering to the sick and lost people all around me: here, have me, eat me up and spit me out if it gives you the sustenance you need to go on. Or stomp on all my well-meaning intentions if it gives you joy, make art out of the energy you take from me, or make nothing and line me up with the rest of the empty bottles and watch me fill with rain.

I put VALIS aside for many years, but never got rid of it, taking it with me from apartment to apartment. At some point it made it back on to the shelf, although for a while I had it turned around, so that just the anonymous white pulp of its pages faced out to the world. One afternoon I said to myself, fuck it, and sat down and quickly skimmed through the second half, where I was relieved to find that Horselover Fat didn’t off himself as I’d feared.

I went back and read it through from the beginning, which took me over a year, since I was very busy and only read it when I was stoned, which was anytime I wasn’t working (and often when I was). I read a few pages at a time and took scraggily notes on how they synced up with my life, without ever coming to any conclusions as to how it managed magically to do so, all these years after my encounter. Was it a cypher, a portal? A cursed pile of words? I had no idea. I simply made note of it.

I didn’t know it at the time, that this act of reading and concentrating on just a tiny bite size chunk of the text would mirror the work I do now, except without the weed.

Eventually I got all the way to the end. And after a lot of thinking and going back to reread various sections, I finally got what the book was about--or so I thought. One key was the movie, Valis, a sci-fi film starring a rock star named Mother Goose which the characters in the book go to see and experience it syncing with their life. Valis the movie is an artsy, nearly nonsensical collage of images paired with chakra-opening sounds (that we as readers obviously can’t hear but are described in such a way that ensures the effect is the same) that make up a film inside a book inside a mind busted by drugs and stress that was longing to break free and that was now read by another mind busted by drugs and stress and longing to break free, neither of them sure if it was even possible.

It was truth—not as a something that could be stated outright with words but as a personal experience of unveiling, of finding oneself in the story.

Having done this work on VALIS as well as having read a bunch more books in general than Odious, my immediate reaction was one of annoyance, when, a few weeks after their solstice dream, they said to me, “I think you’re finally ready to read VALIS.” They had called me into the living room where Fight Club was on mute on the big screen.

“I’ve already read it—several times—as I told you,” I said, worried about how they seemed to be forgetting stuff more and more.

“Yes, but you were a different person. You may have read the book, page by page, cover to cover, and experienced its strange effect. But back then you only saw the maze--now you’re ready to free yourself from it.”

There was that word--free. At once so exhilarating and terrifying, which is why I hadn’t used it myself in years.

“But how do I do that?” I said, my heart pounding.

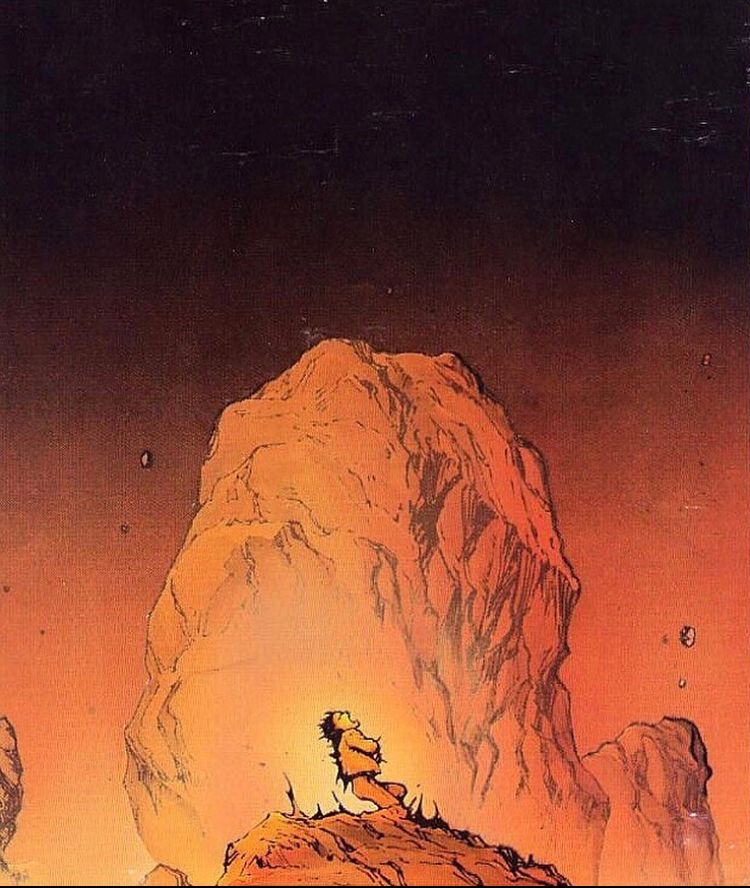

“By learning how it moves when we move. PKD quotes Parsifal in the book about the difficulty of solving a maze that moves. It makes us feel like we’re walking forward when we’re really in the same place, and that we’re standing still when we’ve already moved a great distance.”

“Because a fixed position is an illusion?”

“Nah, because the maze is alive.”

Image: Katsuhiro Otomo, "Akira Cover #11"

Please subscribe and share this post and write to me at odiousawry(at)gmail(dot)com or visit me here with any questions or comments.